Arc is critical in stories. How do the characters change? Who changes and how? What is an arc and do we need a protractor?

In my last post, Personality Traits: Creating Dimensional Characters, we talked about how useful personality tests can be for character creation and balancing the party.

Ideally, we want to have a nice mix of personalities that compliment each other. But, it’s also critical they all generate conflict lest we end up with a snooze-fest.

Stories offer an escape, provide entertainment, teach, and promote introspection and examination. Most importantly, stories expand on the human condition and show us change is possible.

For the record, feel free to skim this post for the highlights. I LOVE examples because that’s how I learn best, and I worked very hard to offer a wide variety of illustrations to demonstrate my points.

Moving on. People change, and…

This change is called arc, by the way.

Granted, there are some characters who never change but they remain the same for an important reason. They’ll act as the lever that forces those around them to arc.

Think Jack Dawson in Titanic or Captain Jack Sparrow in the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise (total coincidence I have two Jacks, for the record).

These characters introduce drama, adventure and chaos into the lives of those around them, people who probably never would have changed had they not crossed paths with one of the Jacks.

Rose would have dutifully married her betrothed Cal Hockley. She’d have lived within the rules, confines and expectations demanded of a lady of her station.

Blacksmith Will Turner, too, would have lived out his life the way social convention dictated. He’d have gone to his grave wondering what might have been. His secret love—the governor’s daughter—would have forever remained that…a secret.

It is only when bad men kidnap Elizabeth Swann and Captain Jack Sparrow subsequently crashes into Will Turner’s life that everything changes.

Mach-IV and Belief

Last time, I introduced the Mach-IV test. The Mach-IV test measures how Machiavellian a person is. High-Mach people tend to be very practical, cynical, ruthless, and highly analytical (they also get a bad rap as all being heartless sociopaths, which is grossly inaccurate).

Low-Mach people generally are more emotional, tend to see the world with rose-colored glasses, believe in the benefit of the doubt and the inherent good of humanity (but they can also be naive and easily duped).

Unlike other personality tests like Meyers-Brigg or the Enneagram test, the Mach-IV changes.

I was an ENFP/INFP in high school, college and today (I score dead even on introvert/extrovert so it is a toss-up). Time, experience, victories and defeats have had little impact on my core personality.

But the Mach-IV is different. It measures how a person sees the world. So say a person generally believes humans are good. They feel honesty is the best policy. They’d NEVER flatter someone in power to manipulate a result.

Nothing wrong with that.

Now toss this person into an unexpected war (or other massive crisis). The person who’d never lie, cheat, steal or manipulate before the life-altering event suddenly has to make some tough choices. Survival is on the line.

Those Who Can’t and Those Who Can

There are those who can change (arc) and those who can’t. These static characters are great for generating tension, but they need to either be limited or offset by more reasonable characters.

Some people, when crisis hits, don’t, can’t or won’t change. Often these people die. At the least, they can put everyone around them in danger.

Depending on your story, the person who refuses to compromise can be an incredible source of tension. This character can exist on either extreme of the Mach-IV spectrum.

Think of a band of refugees running from an invasion who are trapped with the person who cannot ever tell a lie.

Fellow D&D nerds? This is Lawful Good.

Either they can’t lie (some people can’t, which is why they suck at poker) Or, they won’t. Maybe they have strong moral or religious convictions.

If your band of heroes decides to take this person into their party, then they are automatically handicapped. They’re going to have to make sure they can run interference. For instance, if this pathologically honest person is questioned at a checkpoint, everyone could die.

If it would serve the group to sneak up on a guard and stab them in the back, the other characters (Iron Man) will likely have to distract or offset our White Knight who’d never abide by this behavior (Captain America).

A rigid moral compass does little to help expedience.

See, there is nothing wrong with this noble character if used, or offset properly.

We can flip the script and have a super High-Mach person who acts on their impulses. This character believes the ends justify the means and can be extremely chaotic. It’s also hard to trust this person even if they’re very effective. This is when the Low-Mach (Captain America) can offset the chaos of the High-Mach (Tony Stark).

Arc: Changing a Low-Mach into High-Mach

So, if you look at our Low-Mach and our High-Mach, they make for great static characters who can drive change in those around them.

Just note, High-Machs and Low-Machs CAN CHANGE (and it’s really fun to watch them transform).

We can arc a Low-Mach into a High-Mach. Think Sarah Connor in the Terminator franchise. She goes from being a simple waitress who believes what she sees into a one-woman killing machine.

In the beginning, her world is a normal, boring routine. Likely her days are much the same…until a man from the future careers into her life to protect her from a murderous cyborg.

Sarah MUST change if she a) hopes to survive b) hopes to protect her unborn son c) hopes to save the world.

Sarah Connor is a fascinating study in that she arcs from being about as Low-Mach as one can get into a metaphorical representation of the very machine she’s sacrificed everything to destroy.

Think of how Reese explains the terminator:

Listen, and understand. That terminator is out there. It can’t be bargained with. It can’t be reasoned with. It doesn’t feel pity, or remorse, or fear. And it absolutely will not stop, ever, until you are dead.

Kyle Reese in “The Terminator”

This is Reese’s description of the cyborg in Terminator. BUT, how much does this LATER describe Sarah Connor in the sequel, Terminator 2?

Low-Mach to High-Mach an Easier Sell

I believe it is actually easier to arc a Low-Mach to High because that is a character most people will feel comfortable with in the beginning.

Since most people fall in the Low-Mach or at least the middle of the range and VERY FEW score as High-Mach, this character is an easier sell.

Why? They look like and think like most people, so it’s easier to get the audience to like them and empathize. Sarah Connor would have never become so iconic had we met her in her 2.0 version. A naive, struggling waitress is a better place to begin.

Other great examples? Buffy in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the group of regular teenagers in Red Dawn, and love interest Dana Cummings in The Accountant.

What about the opposite? High-Mach to Low-Mach?

I don’t believe it’s possible to have the extreme changes going COMPLETELY the opposite direction. It’s much more reasonable for a naive goody-goody to turn very dark than it is to turn someone very dark into a total goody-goody.

Not impossible, merely easier.

One is believable, the other requires either something akin to a Road to Damascus experience, or a trial by fire brutal enough to soften even their hard hearts.

For instance, Road to Damascus moments happen. We have Scrooge in A Christmas Carol. His life might not be on the line, but his salvation is.

What about a former drug dealer who nearly dies after being shot, who then becomes a street minister? A notorious cyber-criminal who changes sides and uses his knowledge to fight bad guys like HE once was? Maybe a hardened prostitute who stumbles across an abandoned baby and it changes her life?

Get CREATIVE!

Don’t have a near-death-revelation to work with? No problem. We ALSO have the massive trial by fire. Life just turns on the heat until the High-Mach softens up.

High-Mach people just aren’t going to suddenly believe the world is all essentially good and see only kittens and unicorns.

While we cannot completely change a them, we can chill them out. We can make them at least a Lower-Mach.

Sherlock (the BBC version) is a good example I introduced last time. By adding in foils like Watson, Lestrade and Molly, Sherlock Holmes arcs and evolves over time into a kinder, gentler prickly pear.

In the beginning, he is solitary, friendless and acerbic to the point of being his own worst enemy.

By the end of the series, he is still Sherlock, but without all the hard edges and points. He’s no longer alone, experiences a semblance of love, and has emotional attachments with the very people who loathed him in the beginning.

He’s even willing to die for them.

While I feel this is tougher arc to write well, if we pull it off, it makes for some of the most timeless stories.

Examples

One of my favorite examples of a High-Mach to Lower-Mach? Gran Torino. Walt Kowalski is an angry, racist Korean veteran who’s transformed when he stands up for his Hmong neighbor against a local gang…the same neighbor who tried to steal his beloved car.

Kowalski is a miserable human being, but when he chooses to try and reform the teen, Thao, he gets more than he bargained for.

By getting involved with his Korean neighbors, he comes to grips with the pain and loss that’s been driving his racist attitude. He becomes a better person.

Walter serves as a surrogate father to Thao who’s heading down a path that leads only to prison or death. Thao, in turn, transforms Walt’s heart of stone and restores his humanity.

Another fab example? Melvin Udall, the misanthropic romance author in As Good as It Gets. Udall is a miserable jerk who suffers from debilitating OCD. He has no use for humans and, frankly, they have almost no use for him.

It is only when Melvin’s gay neighbor is the victim of a hate crime that we see Melvin begin to defrost. Between that and his relationship with his favorite waitress and her son, Melvin transitions from utterly irredeemable person to someone we eagerly root for by the end.

The Trick to High-Machs

As I mentioned earlier, High-Machs can be a tougher sell. We have to hook the reader early and hook hard. If our character is too off-putting, then that is no good.

We can do something that humanizes an otherwise unsympathetic character.

With Marvin Udall, the writers humanized him by showing his paralyzing OCD and the impact it had on everyday life. Yes, Udall is a b@stard, but when his world doesn’t perfectly line up? He’s a lost, frightened child.

What better way to SHOW (not tell) Melvin’s arc—how he has CHANGED—than have him curled up with his neighbor’s dog, the same dog he tossed down the garbage chute in the beginning of the movie?

We can also use supporting characters to keep the audience vested long enough to start caring for our High-Mach character. This is evident in A Christmas Carol—we care about Bob Cratchit even if we have no use for Scrooge.

Why do audiences love to see High-Machs arc to Low(er)-Machs? We all want to believe in redemption.

Save the Cat

We can also inject what the late, great screenwriter Blake Snyder referred to as a “Save the Cat” moment. Christian Wolff, the CPA/hitman in The Accountant is, on the surface, like trying to relate to a robot.

Not only is Christian’s backstory brilliantly woven throughout the movie, but in the VERY BEGINNING we see him helping an aging couple with their taxes.

He uses his supercomputer brain-powers to navigate tax law and make sure the couple doesn’t lose their farm to the IRS. While not evident in any of his body language, we sense he really does care. Soon after this event, Christian literally saves their lives when bad guys come calling.

***Note how his NAME shows what a contradiction he is—Christian Wolff.

How to Arc a Low-Mach to a High-Mach

While this might seem easier to do, we still have to tread carefully. First of all, we need an event or a situation robust enough to fundamentally alter our Pollyanna’s world view. Obviously, war, disaster, famine, etc. are all doable, but there’s no need to be myopic.

Catastrophes that are personal can actually resonate better. Why? Because most people are far more likely to face down cancer than an asteroid hurtling toward Earth.

Why do audiences love to arc Low-Machs to High-Machs? We like to believe in humanity’s capacity to survive no matter the odds. It’s also a solid reminder to be careful how we judge.

We honestly do NOT know how we’d react in any given situation, and these stories and characters keep us humble.

Never say never.

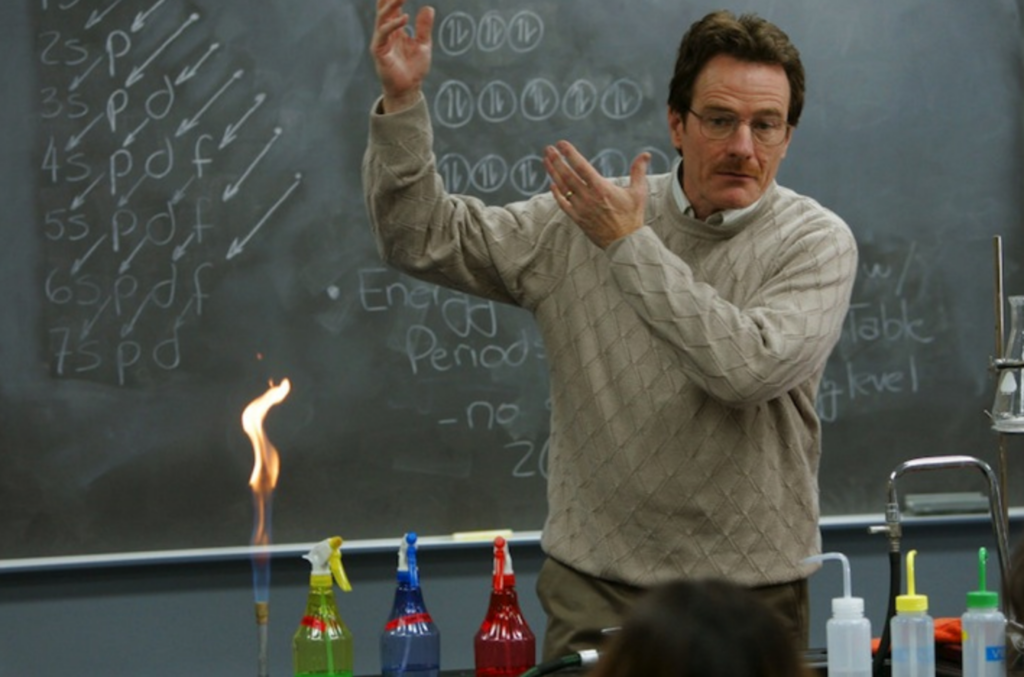

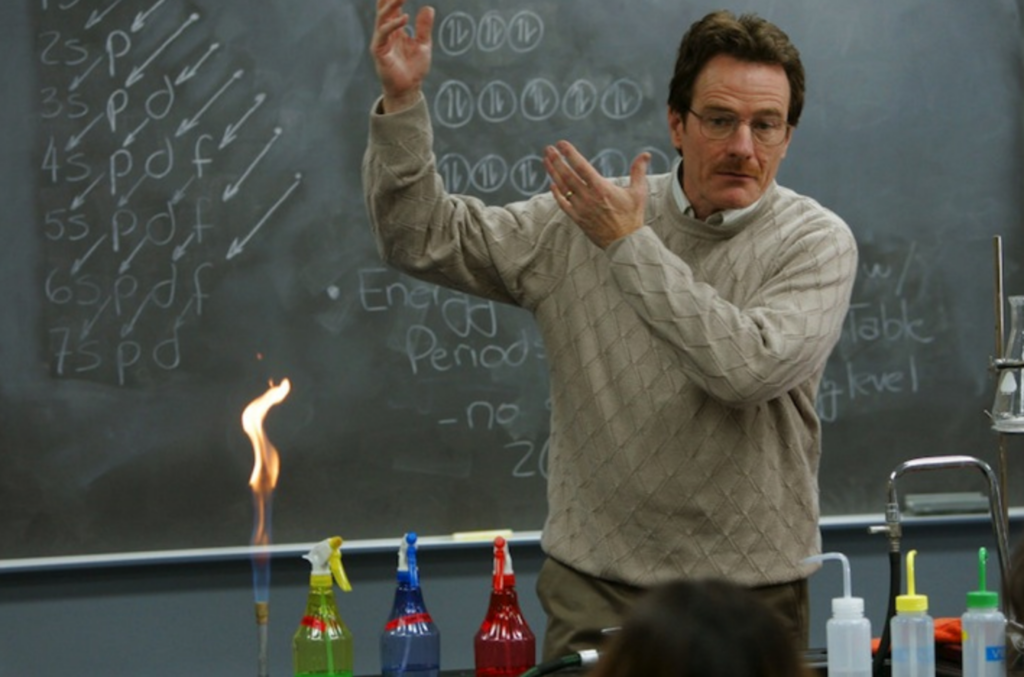

This is why the series Breaking Bad has been so popular. Walter White is a high school chemistry teacher. His son has cerebral palsy. When Walker is diagnosed with Stage III cancer, what does he have to lose?

He uses what he knows best—chemistry—to provide for his family after he’s dead.

Now, do y’all think Walter just woke up one day and thought, “Hmmm, I think I’ll become a drug kingpin”? Of course not. But the sudden deadline—emphasis on DEAD—is enough for Walter to throw away his moral inhibitions for what he sees as the greater good.

Why is this story so fascinating? Because it forces self-examination. We honestly cannot answer if we’d do any better if faced with the similar life-altering events. Stories like these engender self-examination.

Who do we believe we are versus who are we…really?

The trick to arcing a Low-Mach to a High-Mach is the reason must be big enough for the audience to give them a pass. It needs to hit us in our tender parts hard enough to at least rattle our resolve.

Pacing Character Arc

Sure, I suppose it is possible for someone to instantly change, but that is a tough sell. If we look at Scrooge, the entire point of the three ghosts visiting is to soften Scrooge enough so the audience not only wants redemption, but they also BUY his redemption.

Same in the movie Doctor Strange. Hot-shot surgeon Dr. Stephen Strange is the best in the world at what he does…and he knows it.

He’s a hopeless narcissistic jerk.

In fact, his narcissism is what causes the accident that destroys his hands and effectively takes away his superpower. Losing his status is the only thing that can humble him enough to seek help that isn’t based in science.

He must reach out to those he once mocked. But it isn’t easy. Strange doesn’t show up Day One at the temple in Nepal and the monks instantly agree to make him whole (or actually better than whole). Strange remains a skeptic (and a jerk) for much of the movie.

That is, until he arcs.

Granted, he’ll always be an egomaniac, but he finds a purpose that is greater than simply serving himself. He ego is channeled to service above self.

Arc & Kubler-Ross Stages of Grief

Character arc also needs to happen organically. Often the change will follow the Kubler-Ross stages of Death and Dying: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance.

The stages don’t need to neatly go down the line. In fact it is highly common for someone to make progress only to suddenly regress. They might seem to reach acceptance only to go back to bargaining.

By using these stages our character’s arc will feel more authentic. Few people are hit with a life-altering event and jump all the way to acceptance. That just doesn’t happen or happens so rarely the audience won’t buy it.

Denial: This isn’t real. Stuff like this doesn’t happen. This can’t happen to ME.

Anger: What did I do to deserve this? This isn’t fair. How can you expect me to do X?

Bargaining: Okay, things are bad, but there has to be another way.

Depression: How did I get here? Will I ever be the same? Who am I?

Acceptance: Gotta do what you gotta do. I need to change.

I guarantee if you look at your favorite movies, you’ll see this pattern. It might even be subtle, and generally is best if it is lest it come across as stilted or preachy.

Mach-IV and Romantic Arc

One of the commenters (Barbara) asked an excellent question about the Mach-IV scores in the last post. She wanted to know if/how it could be used in a romance. Hopefully, by now, y’all can see how the Mach-IV scale is used in all genres, but romance probably already applies it quite liberally.

How many Hallmark movies revolve around the sweet, sensitive handyman melting the heart of a no-nonsense corporate lawyer and reminding her of the true meaning of puppies, Christmas, then finally love? Or the scatter-brained but tenderhearted nanny who shows the hard-nosed diplomat it is okay to love again after losing his wife?

How many staple romance characters are deeply wounded? They’ve vowed to never love again. They refuse to ever be vulnerable again. Maybe they have a dangerous job or shady past and so they keep everyone at a distance.

Perhaps one of them is seemingly ‘incapable’ of love. In fact, emotionally unavailable men have been a staple of romantic characters since Mr. Darcy at least.

Why do y’all think I have been crushing on Sherlock?

There is a whole canon of fanfic (Sherlolly) devoted to Molly Hooper and the emotionally handicapped Sherlock Holmes finding love together.

Personal vows are a big deal in romance.

Though I don’t want to be overly reductive because romance is a vastly complex genre, the whole POINT of romance is a) opposites attract and b) showing love wins. If there were no barrier to love in the beginning, then we have no story.

The larger the barrier, the more insurmountable the odds, the better the story.

Obviously the two partners are going to have to alter their worldview if they hope to find love. In romance, the love interests are going to have to arc and meet somewhere in the middle if they hope to find their HEA (Happily-Ever-After) or the more contemporary HFN (Happily-For-Now).

What Are Your Thoughts?

Enjoy your Spring Break for those who have that right now. Do you now understand what arc is and how to do it well? At least a little better? Who can add examples from film, television or movies?

What are your favorite High or Low-Mach characters? Do you prefer resilience stories or redemption stories? Or do you love both?

So again, any thoughts, questions, opinions? I do love hearing from you.

What do you WIN? For the month of MARCH, for everyone who leaves a comment, I will put your name in a hat. If you comment and link back to my blog on your blog, you get your name in the hat twice.

What do you win?

The unvarnished truth from yours truly. I will pick a winner once a month and it will be a critique of the first 20 pages of your novel, or your query letter, or your synopsis (5 pages or less).

***I will announce previous winners next post and will have new classes available soon. Still getting over COVID so getting there, slowly but surely.